New York

Working Conditions

Body

In the nineteenth century, most new immigrants were unskilled laborers. Many found jobs in the factories of New York City, Buffalo, and other cities around the state. Jobs were plentiful in the industrializing American economy, but the low pay, long hours and deplorable conditions fell far short of the immigrants’ expectations.

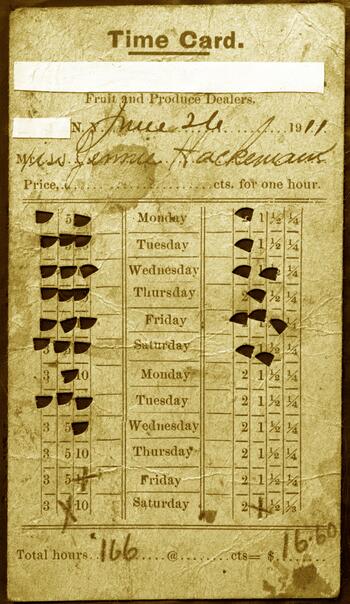

Young children were forced to forego the opportunity of a free public education so that they could work to help support their families. Much to the dismay of progressive reformers, immigrant parents often forced their children to drop out of school so that they could be put to work in mines, mills, factories and farms.

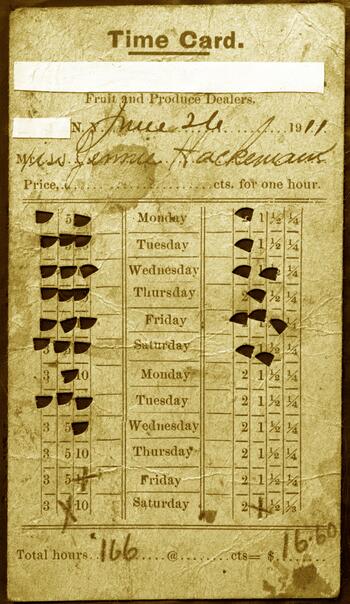

Factory management insisted on adherence to timecards, a modern and foreign concept to immigrants from rural areas who were more accustomed to keeping pace by the agricultural cycles. Sharing an enclosed work space with other workers, surrounded by loud mechanized equipment, and overseen by demanding management added to the immigrants’ discomfort as they sought the American Dream.

Outside of factories, options for unskilled laborers in the late 19th century included manual labor such as digging sewer and roads, collecting garbage, and working construction. Immigrants also served in New York’s most dangerous occupations, such as firefighting.

Employers took advantage of the most recent immigrants, who were often referred to as “greenhorns.” Businesses often hired them to perform the most menial jobs and paid them less than other workers for “training.” Workers laid off during slow seasons or slack time did not receive any pay while they were out of work. If workers spoke up about their low wages, excessive hours or conditions, they found themselves blacklisted and branded as troublemakers, making it impossible to find employment.

Women who encountered sexual harassment from their supervisors kept silent for fear of losing their jobs. Some women became so desperate that they entered into prostitution or, as it was commonly known, “white slavery.”

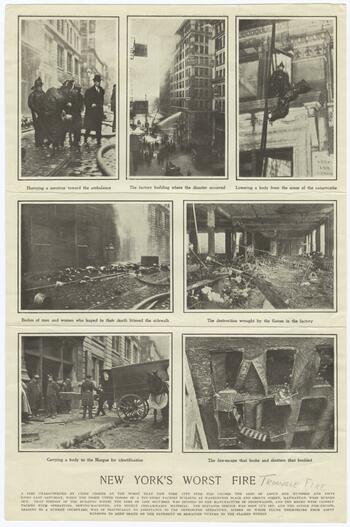

Garment workers often worked for piece rates, making a fraction of a cent for each piece of garment they finished sewing, usually by hand. In March 1911, 146 young immigrant women died at the Triangle Shirtwaist Company in New York’s Greenwich Village, exposing the horrendous factory conditions to the nation and prompting public demands for reform.

Following the fire, New York State legislature formed a Factory Investigating Commission in 1912 to investigate workplace conditions. The commission’s six-volume report took three years to complete and resulted in over thirty workplace safety laws that continue to impact workers today. New York State became a leader in the area of industrial safety reform and many of the progressive reformers, including Frances Perkins, who served on the commission, forged careers in politics and government further advance that cause.

Image & Captions:

Item Image:

Item Caption:

Women pose in a hop field during harvesting, circa 1880, courtesy of Fenimore Art Museum

Late 19th century Otsego and Madison Counties were known for producing “King Crop”: hops for brewing beer. Most of those hops were picked by migrant families in August and September. Employers favored young people, especially girls, for the work because hop picking relied on nimble fingers.

View item information

Item Image:

Item Caption:

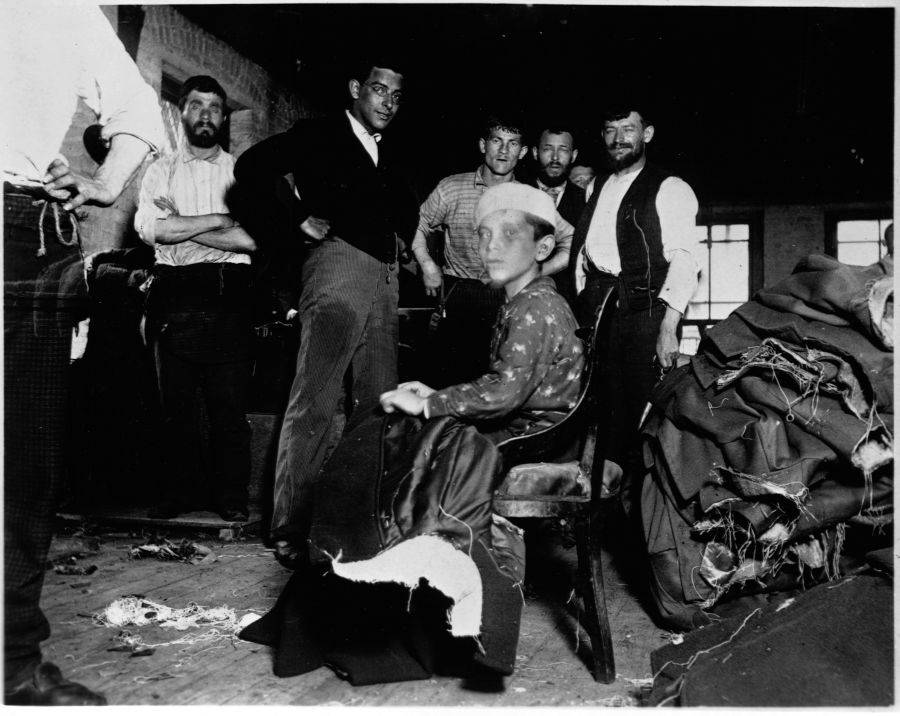

School Year Repeaters, 1910, courtesy of Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, National Child Labor Committee Collection, [LC-DIG-nclc-00780].

Sarah Saneri, Lucy Martina, Carmelo Castanzo, and Josephine Guercio are all repeating a year of school, having missed 11-13 weeks each while working in canneries and factories. They lived in the crowded, predominantly Italian Canal District of Buffalo. Lucy, 16, and Carmelo, 12, were both born in Italy.

View item information

Item Image:

Item Caption:

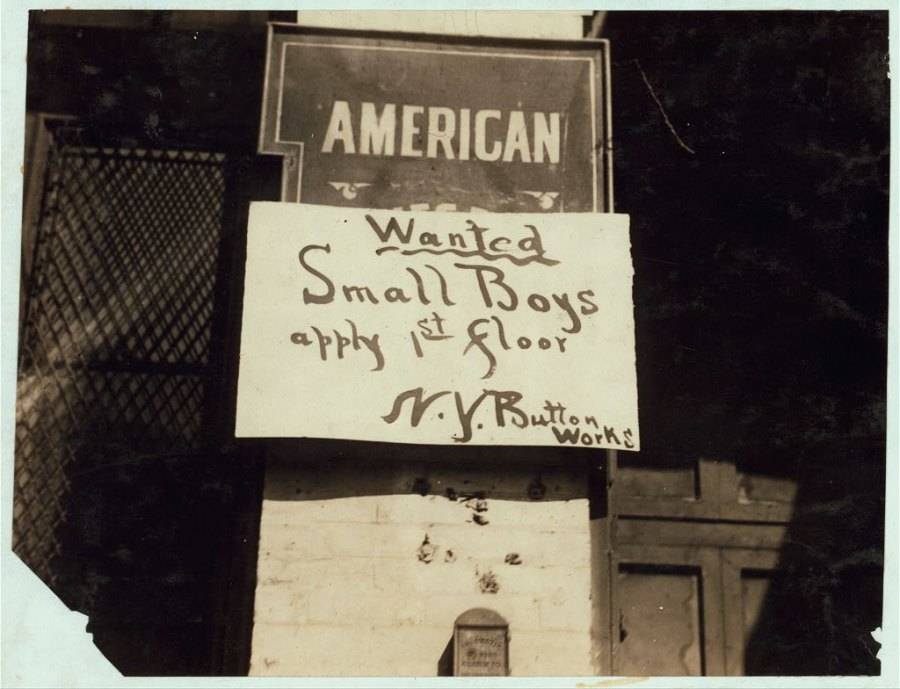

Time card for 117 hours, courtesy of the New York State Archives

Time card from 1911 for Miss Jennie Hackemans, who worked for 166 hours over two weeks and earned $16.60 for her efforts.

View item information

Item Image:

Item Caption:

Malachi Kraham, Chief, Neptune Company #3, 1885, courtesy of Fenimore Art Museum, Cooperstown, New York. Smith and Telfer Glass Plate Negative Collection. Gift of Arthur J. Telfer. N0226.1951.

Malachi Kraham, born in Ireland in 1844, immigrated to New York in 1859. He and his Irish-born wife Johanna Malloy raised eight children on his income as a grocer, and he served in the Otsego Fire Department as well.

View item information

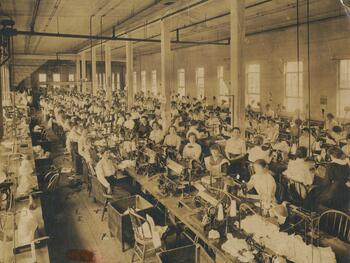

Item Image:

Item Caption:

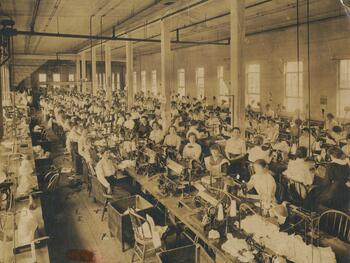

F. Jacobson and Sons, 77 Cornell Street, Kingston, New York, circa 1920, courtesy of Friends of Historic Kingston

Employees at F. Jacobson and Sons work on sewing shirts. The Kingston F. Jacobson and Sons was opened on February 13, 1917. The company had factories in Delaware, Maryland, New Jersey, and New York.

View item information

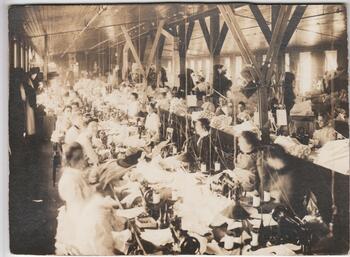

Item Image:

Item Caption:

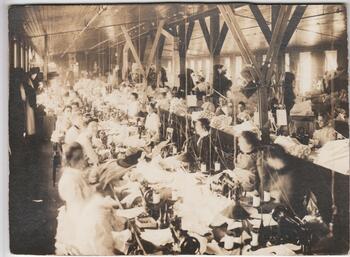

Empire Corset Co. Sewing Division, McGraw NY, courtesy of McGraw Historical Society

The sewing machine division of Empire Corset Co. was mainly staffed by women. McGraw, NY, in Cortland County, was referred to as "Corset City" in 1898.

View item information

Item Image:

Item Caption:

Willowvale Bleachery/sewing room, New Hartford, NY, courtesy of New Hartford Public Library

Women pause from production in the Willowvale Bleachery's sewing room in New Hartford, while their male supervisors stand behind the work tables.

View item information

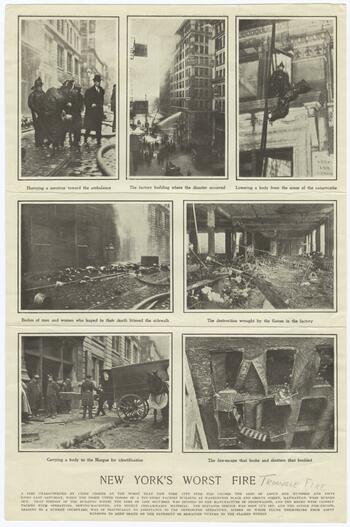

Item Image:

Item Caption:

New York’s Worst Fire, 1911, courtesy of Columbia University Library

Harper’s Weekly published many photographs from the Triangle Shirtwaist Fire, including those of bodies on the street. Frances Perkins kept a copy of this page in her personal files.

View item information